In the last year, I’ve noticed a reclamation of an old feminist term on social media: the male gaze, generally contrasted with the female gaze. I initially saw the female gaze crop up to talk about writing male romantic characters specifically to appeal to women. But the more dominant usage has become to talk about the way women dress, from styling to shape to the purpose of clothing.

Dressing for the female gaze, as best I can tell, means wearing looser clothing, lots of layers, and not showing much skin. Women post before and afters, with tight clubwear when dressing “for the male gaze,” versus a carousel of voluminous layers after deciding to dress for the female one. One example of an outfit instruction “for the female gaze” is a maxi skirt, oversized knit sweater, and bold or chunky shoes. The outfits feel neutered, as if the female gaze is somehow above sexuality. It’s not that they don’t look cool, but these outfits would pass muster at any modesty check at your local church youth group.

The male gaze, which the female gaze turns on its head, is a theory rooted in media studies and feminist film theory about cinematic interpretations of women and women’s bodies. Laura Mulvey coined the term in her essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1975), which takes a very Freudian, psychoanalytic approach to women’s representation in film. The male gaze is not just about how heterosexual men view or think about women; it is a triangulated gaze between the camera’s looking, the characters looking at each other, and the audience looking at the film itself. Mulvey describes this phenomenon in film as a form of pleasure in looking at another person as an erotic object.

This idea caught fire, and female filmmakers began to dissect what they saw on screen and create their own approaches in opposition to this idea. Agnès Varda, a filmmaker interviewed in Filming Desire, describes what she has observed about how men depict women in films: often as pieces of the body instead of the whole (especially, in her words, “erogenous zones”); when naked, they must immediately engage in sexual activities. Instead, Varda says she allows the women in her films space to just exist, naked or not.

What strikes me about conversations on dressing for the male gaze, or the female gaze (when will we invent the non-binary gaze?), is not only the default heterosexuality baked in, but the idea that women are inherently an object to be gazed at. It’s like we can only get a clear view of ourselves by imagining our image in the mind’s eye of someone else. But this isn’t just fantasizing about how you fantasize about me; I think it speaks to a larger phenomenon of forced hypervisibility in the age of increasing surveillance.

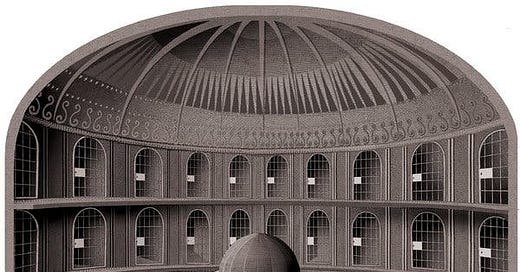

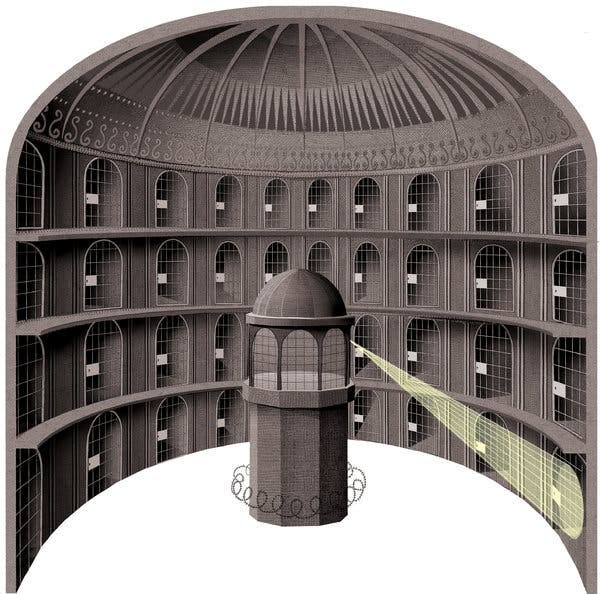

Surveillance culture has made the gaze of the other feel inescapable. Whether we actively participate or not, our data is tracked, our faces scanned, and our backgrounds checked. Social media plays a big role in this too, as an opportunity to broadcast the minutiae of our habits and thoughts. In Mulvey’s original essay, she speaks of the triangulated gaze; now it’s more like a kaleidoscope gaze. Our view of ourselves is fractured and reflected back to us not only through others, but through social media, and how we imagine others might see us through social media, and the ads catered to us, and features like Spotify Wrapped serving our data back up to us on a silver platter. It creates a dizzying and ever-shifting picture. The more we see ourselves, the less sure we are of what we see.

There are no easy answers for opting out of surveillance; it has permeated nearly every facet of modern life. But what would it look like to reclaim our minds, to refuse the idea of being an object to be gazed at all? Agnès Varda says, “The first feminist gesture is to say: ‘OK, they're looking at me. But I'm looking at them.’ The act of deciding to look, of deciding that the world is not defined by how people see me, but how I see them.” This is the primary step in reclaiming one’s self and mind back from oppressive gazes.

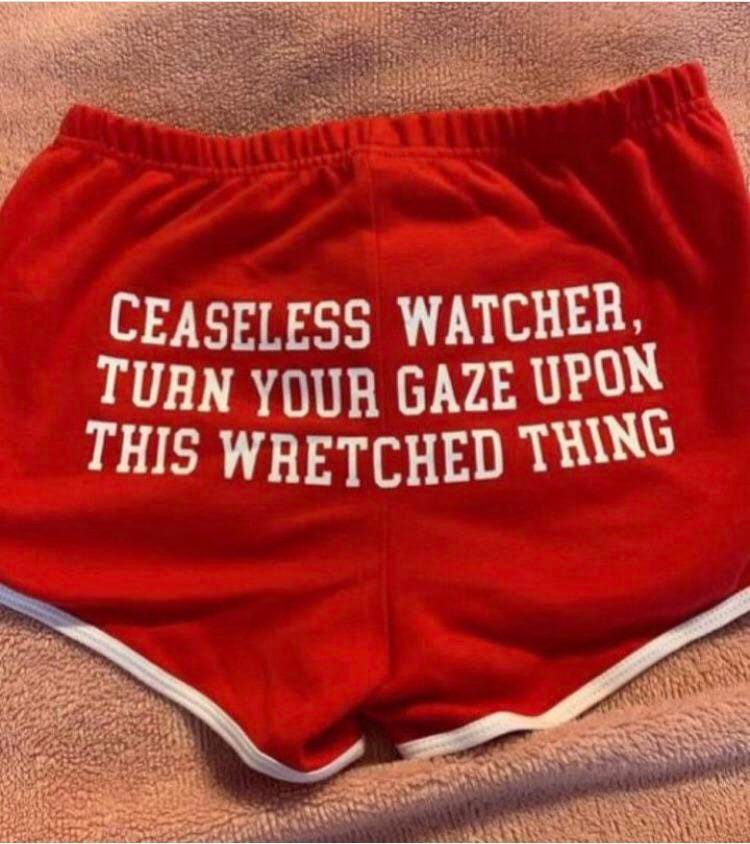

How do you reclaim your mind? I think of Janelle Monáe and her 2018 album and accompanying film, Dirty Computer. The film is a sci-fi story of a society where anyone who is different, or who opposes the status quo, is considered dirty and is subjected to a “cleaning,” or an erasing of their memories and personhood. Janelle and her lovers fight back to keep their memories and escape together to an unknown freedom. One of my favorite concert t-shirts is from this album cycle, and it declares “SUBJECT NOT OBJECT” in bold letters on the front.

A key piece of moving from an object that is observed to a subject who acts is to both know who you are and paradoxically, think about yourself less. You have to get off your phone and leave your house. You have to be around people who are different from you. You have to dedicate yourself to something bigger than optimizing your own body and mind.

Varda resisted the male gaze by refusing to portray the women on the screen in pieces, instead showing them as a whole person. Perhaps we can learn something from this, from stepping back to see our full selves imperfect and complicated, instead of zooming in on what we can control. We can reject the gaze as something that defines us. There is always more to you - and to every person - than what can be seen.